“Old Baldy”

“Old Baldy” General Meade’s Warhorse

A brief history By Anthony Waskie, Ph.D.

‘Old Baldy’, the most famous of the war horses used by General George G. Meade was raised on the western frontier, and brought east as a U.S. Cavalry mount. At the outbreak of the Civil War ‘Baldy’ was ridden by General David Hunter, and at the First Battle of Bull Run, July 21st, 1861, Baldy was wounded on his nose by a piece of shell, and, perhaps also on his flank, as a scar was later visible there from an unknown action. He was returned to the Cavalry Depot at Washington, D.C. to recuperate and return to service. He was, however, afterwards purchased by General George G. Meade, from the Quartermaster Department at Washington, D.C. in September of 1861 for $150, and was ridden by Meade almost exclusively through actions and campaigns through the Battle of Gettysburg, and in the following actions:

Drainsville, Va. December 20th, 1861; Mechanicsville, Va. June 26th, 1862. ; Gaines Mill, Va. June 27, 1862; Groveton, Va. August 29, 1862; Second Bull Run, Va. August 30, 1862; South Mountain, Md. September 14, 1862; Antietam, Md. September 17, 1862; Fredericksburg, Va. December 13, 1862; Chancellorsville, Va. May 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 1863; and Gettysburg, Pa. July 1st, and 2nd, 1863; end of his combat service.

(The following actions are mentioned in the Meade Post #1, G.A.R. History, but are not accurate, as Meade reported sending Baldy home before the commencement of the 1864 Overland Campaign in late April, 1864. The horse confused with Baldy during this latter period, may have been his Brown Morgan): Bristoe Station, October 14, 1863; Rappahannock Station, November 7, 1863; Mine Run, November 26, 1863; Wilderness; May 5, 6, 1864; Spotsylvania, May 8th to 20th, 1864; North Anna, May 23rd to 26th, 1864; Totopottomy, May 29th, 1864; Bethseda Church, May 30th, 1864; Cold Harbor, June 1st to 3rd, 1864; Petersburg, June 15th to 18th, 1864; Jerusalem Plank Road, June 22nd, 1864; Mine Explosion, July 30th, 1864; Weldon Railroad, August 18th to 25th, 1864.

General Meade’s comments on Baldy and his horses (from Life & Letters of General Meade):

Camp Pierpont, VA. November 14, 1861

To son John Sergeant Meade

“I am badly off for horses. The horse (Baldy) I first got has been an excellent horse in his day, but General Hunter broke him down at Bull Run. The other one has rheumatism in his legs, and has become pretty much unserviceable. This has always been my luck with horses; I am never fortunate with them. I should like much to have a really fine horse, but it costs so much, I must try to get along with my old hacks.” (p.227)

Camp Pierpont, VA. November 22, 1861

To son John Sergeant Meade

“As to horses, I did the best I could. The truth is, the exposure is so great, it is almost impossible to keep a horse in good health….I have no doubt you can get me a good horse for $250. I can do that here; but where are the $250 to come from? Remember, I have paid now $275 already.” (p.229)

Camp Pierpont, VA. December 2, 1861

To Mrs. George G. Meade

“The most important piece of intelligence I have to communicate is that I have bought another horse. He is a fine black horse that was brought out to camp by a trader, for sale. I bought him on the advice and judgment of several friends who pretend a knowledge in horse flesh, of which I am entirely ignorant. I exchanged Sargie’s (son Sergeant) horse and gave a $125 boot. As Sargie’s horse cost me $125, it makes my Black (‘Blacky’) turn me out $250, a very high price. But Sargie’s horse was entirely broken down and worthless from exposure, and was pretty much a dead loss to me. I hope my Black will turn out well. Thus far he is very satisfactory, being full of spirit and quite handsome; but there is no telling when you get a horse from a regular trader what a few days of possession may bring forth.” (p. 232)

Centreville, Va. August 31, 1862

To Mrs. George G. Meade

“I write to advise you that after three days’ continuous fighting; I am all safe and well. Old Baldy was hit in the leg, but not badly hurt.” (p. 306)

Field of Battle near Sharpsburg, Md. September 18, 1862

To Mrs. George G. Meade

“I was hit by a spent grape-shot, giving me a severe contusion on the right thigh, but not breaking the skin. Baldy was shot through the neck, but will get over it. A cavalry horse I mounted afterwards was shot in the flank.” (p.310)

Camp near Sharpsburg, Md. September 23, 1862

To Mrs. George G. Meade

“Old Baldy is doing well and is good for lots of fights yet.” (p. 314)

Camp opposite Fredericksburg, Va. December 16, 1862

To Mrs. George G. Meade

“The day after the battle, one of their sharpshooters took deliberate aim at me, his ball passing through the neck of my horse. The one I was riding at the time was a government horse, so that Baldy and Blacky are safe.” (p. 338)

Camp opposite Fredericksburg, Va. December 31, 1862

To son John Sergeant Meade

“George (son of General Meade) has taken a great fancy to a little black mare I have, belonging to the government, which he has given me various hints he thought I might buy and present to him, and in this little scheme to diminish my finances to the tune of $120, he has the hearty cooperation of Master John (Marley) – General Meade’s valet, who informs me every morning he thinks the boy ought to have the black mare.” (p. 343)

Camp near Falmouth, Va. March 13, 1863

To Mrs. George G. Meade

”Yesterday I put the ladies in an ambulance and mounted Captain Magaw (U.S. Navy) on Baldy, and we went over and took a look at Fredericksburg, and afterwards called on Hooker.” (p. 357)

Head-Quarters Army of the Potomac, Gettysburg, Pa. July 5, 1863

To Mrs. George G. Meade

“Baldy was shot again, and I fear will not get over it. Two horses that George (General Meade’s son and aide de camp) rode were killed, his own and the black mare.” (p. 125, Vol. II)

Head-Quarters Army of the Potomac Frederick, Md. July 8, 1863

To Mrs. George G. Meade

“Old Baldy is still living and apparently doing well; the ball passed within half an inch of my (right) thigh, passed through the saddle and entered Baldy’s stomach. I did not think he could live, but the old fellow has such a wonderful tenacity of life that I am in hopes he will.” (p. 132, Vol. II)

Head-Quarters Army of the Potomac, April 24, 1864

To Mrs. George G. Meade

“Yesterday I sent my orderly (George Melloy) with Old Baldy to Philadelphia. He will never be fit again for hard service, and I thought he was entitled to better care than could be given to him on the march.” (p. 191, Vol. II)

May 23, 1864 (not contained in Life & Letters) Thanks to Jim Hueting of Gettysburg

To Mrs. George Meade

“You have never told me anything of Baldy- where he is and how he is getting on.”

Baldy reference June 27, 1864 (not contained in the Life & Letters) Thanks to Jim Hueting of Gettysburg

To Mrs. George Meade

“John Marley” (his groom) is also well, but at present a little anxious about the black horse, whose wounded leg gives signs of again discharging. By the by, what has become of poor old Baldy? Your mother never writes about him and John is of the opinion he is being murdered. John says a closed stable, in his weakened condition, after the life he has led, will most certainly kill him. The last I heard of the poor old brute, he was still at Stetson’s (John Stetson?) and considered too weak to take out to Gerhard’s (Benjamin Gerhard, Meade’s brother-in-law). Do let me know something about him. I was very much distressed to hear of Mr. Gerhard’s death…”

Head-Quarters Army of the Potomac, July 7, 1864

To Mrs. George G. Meade

“I am glad to hear the good news about Baldy, as I am very much attached to the old brute.” (p. 210, Vol. II)

At Gettysburg, General Meade’s famous war horse ‘Baldy’ received a ball in his right side, passing through the saddle flap of General Meade, just missing his right leg, and lodged in Baldy’s stomach. This incident occurred on the afternoon of July 2, 1863 on the left of the Union Army line along Cemetery Ridge. Upon being wounded, Old Baldy refused to move forward for the first time in his service, and had to be retired from the field. Later, Baldy was sent north in charge of George Melloy, of the First Pennsylvania Cavalry, to Philadelphia, by rail, and then sent to Meade’s old friend and former staff quartermaster in the Pennsylvania Reserves, Capt. Samuel Ringwalt who agreed to care for him at his farm in Downingtown. Later, in the post war period, Baldy was found to be sound and was used by General Meade in Philadelphia. He was often seen riding Baldy through Fairmount Park accompanied by his daughters as he surveyed the landscape. (Life & Letters. P. 301) Later Baldy was conveyed to Meadow Bank Farm, where General Meade spent his summers and a country place owned by a friend of the Meade Family, John J. Davis, where he remained for several years. After the death of his master, the faithful old war horse was even able to march in the funeral procession of General Meade on November 11, 1872, when Meade was laid to rest in Laurel Hill Cemetery, Philadelphia. At the grand parade held in Philadelphia in 1879 upon the return of former president Grant, an old comrade of Meade, ‘Baldy’ was a prominent marcher in the spectacle. ‘Baldy’ was then kept by Mr. John J. Davis, near Jenkintown, Montgomery County, Pa. who cared for him until he became too feeble to get up after lying down, and on December 16, 1882, with a dose of poison, laid him finally to rest. ‘Baldy’ was over 30 years old, and had lived ten years after his gallant master, General Meade. He was a veteran of many battles through which he safely carried General Meade. ‘Baldy’ was also wounded in the nose at First Bull Run, July 21st, 1861 when owned by General David Hunter; at Second Bull Run, August 30th, 1862, he was wounded through the right hind leg; at Antietam, September 17th, 1862 Baldy was wounded through the neck, and seemingly left for dead on the field; and at Gettysburg, July 2nd, 1863 he was shot through the body comprising four (4) major wounds.

From Meade’s personal letters, and the description of Col. Meade, the General’s son in 1883, it indicates, however, that he did keep Old Baldy with him after Gettysburg, hoping to see a recovery in his favorite horse, but despairing of improvement, did send him home at the start of the Overland Campaign (“before we crossed the Rapidan”)

The story of Baldy as quoted from the Meade G.A.R. Post #1History does list ‘Baldy’ at battles subsequent to his apparent removal from the front.

I suspect the later report of the veterans is incorrect and may reflect Meade’s use of his other ‘show’ horses: the brown Morgan, whom he calls a ‘racker’, or ‘Blacky’, who was wounded along with General Meade at the Battle of Glendale, June 30, 1862. (Life & Letters, p.298)

I included all the reports in my brief history in the interests of sharing the complete story.

There are also unpublished parts of Meade’s letters of the time of the Overland Campaign to his wife asking about ‘Baldy’ and of his progress.

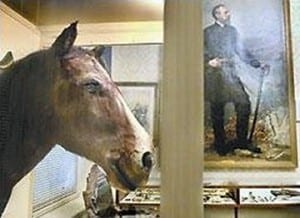

The comrades of the Meade Post #1, Grand Army of the Republic in Philadelphia took the name of General Meade for their Post. At the muster of February 26th, 1883, a very interesting and minute report was presented by comrades Albert C. Johnston and H.W.B. Hervey, the committee, who upon their own responsibility, secured and presented to the Post that interesting and valuable relic “Old Baldy”–the head and neck of General Meade’s old war horse ‘Baldy’–and comrade G. Harry Davis, on their behalf, presented “Old Baldy” to the Post, it having been very tastefully placed upon a tablet, which contains briefly the services of the old horse and an account of the wounds he had received in battle.

The Post gave thanks to Mr. John J. Davis the owner of the horse, for his services in assisting the committee in procuring the relic, as the horse was already buried on his farm, and for a photograph of himself and the horse, which was granted.

Letter of General Meade to Capt. Sam Ringwalt, Quartermaster

Regarding handling of “Old Baldy”

Headquarters Army of the Potomac September 24, 1864

My Dear Friend,

Mrs. Meade writes me that you have kindly consented to receive Old Baldy at your place and I hasten to express to you my very great thanks. The Old Fellow was wounded in the flank at Groveton (2nd Bull Run); was shot through the neck at Antietam, and at Gettysburg a ball passed through the saddle and went into his body where it has remained ever since. I kept him with me until this spring in the hopes he would recover, but fearing he might be an embarrassment in the campaigns, I sent him to Philadelphia just before we crossed the Rapidan. I don’t want you to be bothered, and shall expect you to let me know what expenses he puts you to, that I may reimburse you. I told Mrs. Meade I wanted to have the old horse in somebody’s hands who knew something about him and would not let him be ill used, and I felt sure if you could look out for him, you would. If he continues to improve, and the war lasts, I will bring him into the field again next spring. The ‘Black’ is still my show horse. The wound in his leg which he got at Glendale kept open for about 18 months, but has finally healed up. It never lamed him for a day since Gettysburg, and Baldy’s being out of service, I have bought a large brown horse, said to be a Morgan—a fine strong horse and a great racker. He and the black are my standbys.

I should like very much to see you and have an old fashioned talk on all that has happened since you left. The old Reserves are pretty much all gone. The last that had reenlisted were mostly captured on the 19th of last month in one of the fights on the Weldon Railroad. Major Baird and Captain Adair are the only officers left whom I can see. We have had some very severe fighting on this last campaign, harder and longer continued than any army ever had before. In the beginning and until we crossed the James River, our men behaved splendidly , but the continuance of the campaign, and the hot weather coming on, together with the great losses we have sustained took a little of the starch out of our boys, and they showed signs of fatigue. We have had showers, a good deal of rest, and the weather is getting cool. All we want is to have our thinned ranks filled up and we shall be ready to go at it again and stay at it until we have compelled the Rebels to say they have had enough. But to do this we must have men, and every one ought to use all their influence to send them to us. The Rebels are being exhausted and now is the time to strike the heavy blows.

When this war is over, I am coming up to Downingtown to see you.

Very Truly Yours

Geo. G. Meade

Capt. Sam Ringwalt

The following article appeared in the Philadelphia Daily Evening Telegraph shortly after the death of Old Baldy, and at the time the head had been mounted and presented to the Meade Post #1, G.A.R. at their February, 1883 Campfire. The article contains a large number of factual errors as to the history of his service with General Meade, no doubt due to fading memories, but the article does detail some interesting anecdotes of Baldy’s post war life. It is obvious, that Baldy and his master were revered by the veterans, especially by the Post named in Meade’s honor in his own hometown, and the veterans sought to do both war horse and his master honor by preserving their memory.

The Daily Evening Telegraph Philadelphia, Tuesday, February 27th, 1883

“Old Baldy”

A memento of General George Meade’s warhorse presented to Post #1, Grand Army of the Republic

At a meeting of George G. Meade Post #1, G.A.R. held on Monday, February 26, 1883 at the headquarters, Eleventh and Chestnut streets, Comrades Johnson and Hervey presented the head and neck of General Meade’s old war horse ‘Baldy’ beautifully mounted.

The history of this animal was somewhat peculiar, as he had first been the property of Colonel E. D. Baker, of the 71st California (Pennsylvania) regiment, and had been badly wounded in the nose at the Battle of Ball’s Bluff, where his master at that time was killed. (This is obviously incorrect. The veterans have confused the wounding of horse and rider: General David Hunter at the First Battle of Bull Run with the death of Colonel Edward Baker at the Battle of Ball’s Bluff, October 21, 1861). After the Pennsylvania Reserves took the field, the horse came into the possession of General George Gordon Meade, and was ridden by him, when circumstances would permit, throughout the entire war (sic). His wounds were six (sic) in number, and at the Battle of South Mountain he was shot and left on the field for dead (The author means: Antietam). Some two or three days after, when a burying party visited the field, Baldy was found grazing on the hillside, and but little hurt from his wound. On four other occasions was he hit, but survived each wound, and returned with his owner at the conclusion of the war. He was getting old, and for the good he had done, he was left on a farm in the vicinity of Jenkintown, to work no more until death released him. He was 30 years of age when he died. Many anecdotes are related of him, and to Mrs. Davis, under whose husband’s charge he had been for a long while, are we indebted for the following incident, which took place last Fourth of July (1882). He had long been stiff, and was seldom found standing up, but on the morning of the nation’s birthday, kicking was heard in the stable, and, on proceeding tither, Old Baldy was found standing up in his stall, and looking as though he would like to go out. The stable door was that once opened, and Baldy marched out. He looked around for a moment, and on seeing the flag which he had followed so long floating over him, he sprang like a colt from his halter, and for some minutes pranced up and down the lane, only to lie down with exhaustion at the end of his gallop.

At last old age overcame him, and for some weeks before his death it was necessary to carry his food to him. On the 20th of December (1882) (sic) he breathed his last and was buried. On Christmas Day comrades Johnson and Hervey visited the farm and were shown his grave.

Proceedings were at once instituted to exhume the body, and in a little while that portion of the noble animal which now adorns the post room was in the hands of the committee. After considerable labor the head and neck were mounted on a slab, with the name and history of the animal emblazoned on its sides, and a laurel wreath tastefully ornamenting the neck. The figure has been tastefully hung on the walls of the post room, and the presentation was made in a Campfire abounding with music and a drum recitative by Master Harry Wolfe, aged five years, a really fine affair. At the conclusion of the Campfire, an old-fashioned lunch was partaken of, consisting of hardtack, pork, beans, and coffee.

Account of ‘Old Baldy’s Death

Public Sprit of Jenkintown, PA December 23, 1882.

General Meade’s Warhorse – The Veteran Charger Killed by a Dose of Poison

After Gallantly Bearing His Master Through Many a Battle in Which He Received Honorable Wounds, the Old Horse Meets his Death.

Brave Old Baldy breathed his last on Saturday (December 16, 1882). He had attained a ripe old age, but with the autumn of his days came infirmities, the unfailing inheritance of horseflesh as of poor humanity. No roll of musketry pealed forth over his newly-made grave, no clang of arms or roll of cannon announced that the brave old war horse had been laid to rest beneath the gnarled apple tree that stands mute sentinel alongside his place of sepulchre.

After playing a prominent part in a score of deadly frays, oft wounded by bullets aimed at an even nobler mark, the veteran lived to survive his heroic master a full decade, and on Saturday (December 16, 1882) a dose of poison from a friendly hand laid General Meade’s favorite charger to rest.

It was in the rear of the blacksmith forge of John J. Davis, who plies his trade alongside his comfortable homestead near the old Abington (Friends) Meeting House that the curtain fell on the last scene of Baldy’s notable career. Before General Meade’s death he gave his old charger to the blacksmith on the condition that he would never sell him into servitude, and that when he was no longer able to perform the light duties that Davis imposed upon him, a friendly bullet or a dose of poison should lay him to rest.

Baldy Decorated

The gift was the outcome of a flattering incident in Baldy’s career. General Meade often occupied during the summer months a house just outside of Jenkintown (Meadow Bank), and his old favorite was always stabled there. One day, a groom took the horse to Davis’ forge to be shod. The blacksmith’s daughters, hearing of the distinguished visitor to the smithy deftly twined a garland of flowers for the warrior horse, and decorated with a wreath, he returned to the general’s home. When returning to the city, he sought a home for his favorite charger, and as Davis had said he should be proud to take care of Baldy if ever his master parted with him, the old fellow found a home at Abington. He lived to be more than thirty years old, and but that of late an affliction of the forelegs has increased to such an extent that he could no longer get up without assistance, he would have been welcome to his comfortable stall until in the natural order of things he departed for the happy hunting grounds. A few days ago, however, it was decided that the kindest act that could be performed for Baldy was to put him quietly out of the way. The services of Dr. D. Davis, the well known veterinary surgeon of Jenkintown were called for and on Saturday at midday the old horse was led out of his stable for the last time. There was grief in the Davis household as Baldy stood shivering in the cold, peering curiously at Dr. Davis as he placed a halter around his head and proceeded to lead him to the place of execution. Mrs. Davis could not stand by and see the death of the brave old fellow, and as the mournful cortege composed of the veterinary surgeon, a well known physician, and a representative of the Public Press accompanied Baldy across a field to the rear of the forge to the foot of an apple tree beneath which a deep hole had been dug to receive his body. Not a work was spoken. True, it was only a dumb animal that was about to stagger, fall and die beneath the deadly action of the potent drug. Yet the mind would conjure up a widely different scene in which Baldy, gay in the trappings of war, with proudly arched neck, heaving flanks and panting nostrils bore amid the clashing of sabers and the hot fire of musketry, the Hero of Gettysburg – Pennsylvania’s noblest son!

The Charger’s Death

The horse looked up with a puzzled air as Dr. Davis clambered up into the tree and made the halter fast to one of the branches, securing his head high up in the air. Baldy in life was as trustful as brave, and he swallowed with all confidence the two ounces of cyanide of potash that was poured down his throat. He took just as readily half a pint of vinegar. The latter liquid instantly freed the prussic acid in the first poison. Baldy braced himself fore and aft, shuddered twice convulsively, and then as the doctor loosened the halter he fell to the ground. A few more struggles and the old war horse stentorously breathed his gallant life away.

Baldy was bred in the ranks. He was a handsome brown horse with four white feet and a white blaze on his face. He was deep in the brisket, had a grand forearm, a rare set of legs and a small, well shaped head neatly set on an arched neck. If there was a fault in his formation, it was his unusual length of barrel, but his truly formed legs were in his best days well able to carry him to victory and glory. The horse was originally the property of General Baker (sic), who rode him in the engagement at Drainsville, Va. (sic), and in the First Battle of Bull Run (sic). General Meade bought him for $150 at Washington, D.C., and bestrode him on two days of the Seven Days Battles that began at Mechanicsville, Va. He carried the general in the Second Battle of Bull Run, and received a bullet in the near hind leg. At Antietam, he again carried his master bravely in the fight until felled by a bullet that passed clean through his neck. The general dismounted and left the charger, as he thought, dead upon the field. Later on, however, on again traversing the ground near the spot where the horse fell, the horse was found by John Marley, Meade’s body servant, quietly browsing on the field of battle. At Gettysburg, both Baldy and his rider (Meade) were wounded. A bullet pierced the saddle flap and lodged in the horse, passing between two of his ribs. An unsuccessful search was made for this bullet. The rib where the bullet had deflected was visibly chipped, and Dr. Davis gave it as his opinion that the missile had subsequently worked its way out though a saddle sore.

Public Press

A Brief Account of the story of ‘Old Baldy’ by George G. Meade, Jr. the General’s son to the Meade Post #1, G.A.R. after the horse’s head had been presented to the Post.

Colonel Meade, who sent this letter to the Meade Post at the time of the publication of ‘Baldy’s’ record –

132 South 18th Street, Philadelphia, PA

March 12, 1883

To the commander of George G. Meade Post #1, Department of Pennsylvania, Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.)

My Dear Sir,

I have noticed so many errors in the various accounts of General Meade’s old war horse, ‘Baldy’ that I have prepared for you, from my own personal knowledge, and from some data which I have, the following brief statement. So long as you have deemed him worthy, of the honors paid to him, it is just as well, that you should have his record correct.

Baldy’s first service was that the First Battle of Bull Run, where he was twice shot, one of the wounds being through the nose. He was ridden in this engagement by General David Hunter, Colonel of the Third U.S. Cavalry, commanding Second Division. General Hunter was himself badly wounded in this battle. At this time ‘Baldy’ was probably government property, as General Meade shortly after, in September 1861, purchased him from the Quartermaster Department. From this time on he followed the fortunes of General Meade in the Army of the Potomac.

He was shot in the leg at the Second Battle of Bull Run, though not badly hurt. He was also shot through the neck at Antietam, this wound also approved slight, and he soon recovered. The last and most serious wound he received, on the afternoon of the Second of July, 1863 at the Battle of Gettysburg, General Meade had first ridden up to the front, on the left center, as the reinforcements were being hurried up to the support of that part of the line, the bullet that struck Baldy, first passed through the right trouser leg of General Meade and the flap of his saddle, and then into ‘Baldy’s’ body where it remained. ‘Baldy’ on being hit, came to a standstill and staggered a little but soon recovered. He however could not be got to go ahead and endeavored to turn away to the rear. No amount of urging or coaxing on the part of the General could get him to move on. General Meade then remarked, “Baldy is done for this time; this is the first time he ever refused to go under fire.”, or words to that effect. The general was promptly supplied with another horse, and ‘Baldy’ was led to the rear.

In hopes that Baldy would recover, the general kept him with him until the following spring, though he was never able to use him. Just before the army crossed the Rapidan in May, 1864, fearing ‘Baldy’ would be in the way in the coming campaign, he was sent to Philadelphia and shortly afterward placed in charge of Captain Samuel Ringwalt of Downingtown, Pennsylvania, an old friend of General Meade’s who had served with him in the early days of the war and knew all about Baldy, and who the general was certain would take good care of him. He remained with Captain Ringwalt until after the close of the war, when General Meade returned to Philadelphia in 1865. ‘Baldy’ was found to have entirely recovered and to be in as good condition as ever. The General constantly used him during the next few years, until from hard service and old age; he became unsafe as a saddle horse.

He then presented him to John F. Davis, near Jenkintown, Montgomery County, Pa. who took the best of care of him until his death.

‘Baldy’ had another scar on one of his flanks which was either the second wound he referred to as received at First Bull Run, or was received in some other engagement, and no note made of. Those of your members, who have followed General Meade on his many battlefields from Mechanicsville to Gettysburg, can bear witness as to his being found where the fighting was the hottest, so that ‘Old Baldy’, whom he preferred to ride on such occasions, had plenty of opportunities of receiving any number of scars.

In November, 1872, ‘Baldy’ was present in the funeral cortege of General Meade and followed the body of his old master to his grave. He must have been at least eight years old when he came into the possession of General Meade in 1861, which would make him about thirty (30) at the time of his death.

Trusting that the above account will be of interest to you, I remain

Very truly yours

George G. Meade

From the souvenir booklet entitled “Historic Views of Gettysburg,” published in 1912:

“‘Old Baldy’ died December 16, 1882, and on Christmas day was resurrected by Albert Johnson and Harry W. Hervey, members of Meade Post #1, Grand Army of the Republic, Department of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. They had his head stuffed, mounted on an ebony shield, inscribed with a record of his service, and together with the front hoofs, which were made into inkstands, it was presented to their Post: Gen. Geo. Meade Post No. 1, G. A. R., of Philadelphia.”

Historic Views of Gettysburg – Illustrations in Half-Tone of all the Monuments, Important Views and Historical Places on the Gettysburg Battlefield

Text by Robert C. [Clinton] Miller

Published by J. I. Mumper and R. C. Miller, Custodian of the Jennie Wade House, Gettysburg, Pa.

Copyright, 1912, By J. K. Mumper and R. C. Miller

(as far as can be ascertained, the front hooves were never used as inkstands, and only one of the hooves is known to exist: the one in the collections of the Old York Road Historical Society, Jenkintown, PA. There is a written inscription on the hoof confirming its origin. The other missing hoof was last known to have been in the collections of the War Library (previously MOLLUS War Museum, then on 1805 Pine St, Philadelphia; now the Civil War Museum of Philadelphia), but its present whereabouts are unknown.

An interesting incident at Gettysburg concerning General Meade and a ‘borrowed’ horse

On the afternoon of July 2, 1863, General Meade reacting to a report that indicated that General Sickles’ III Corps, assigned to a position on the left flank of the Army of the Potomac along Cemetery Ridge onto Little Round Top, was out of position, caused Meade to call for his trusted war horse ‘Old Baldy’ to be brought to him, so that he could ride out to the area of contention, and view the lines for himself. Old Baldy was, however, not ready for immediate use, at which knowledge, General Pleasonton, the Cavalry commander, then serving at Meade’s HQ offered his own horse to Meade to use, since he was saddled and waiting. This horse is reported to be named ‘Bill’.

General Meade mounted ‘Bill’ quickly and proceeded to ride out to the new line of Sickles’ Corps to meet the III Corps commander and iron out any expected difficulties. The following episode was observed by a staff officer of Sickles: Major Henry Tremain, who wrote of the incident in his memoirs in 1905:

“Suddenly, a little to the north of where we (Sickles and staff) were standing (thought to be near the Peach Orchard), a small body of horsemen appeared to my surprise on our open field … and at a place of all others most tempting to the enemy’s guns…Rapidly approaching us the group proved to be General Meade and a portion of his staff.

General Sickles rode towards them, and I followed closely, necessarily hearing the brief, because interrupted, colloquy that ensued.

General Sickles saluted with a polite observation. General Meade said: ‘General Sickles, I am afraid you are too far out.’ General Sickles responded: ‘I will withdraw if you wish, sir.’ General Meade replied: ‘I think it is too late. The enemy will not allow you. If you need more artillery, call on the artillery reserve.’

“Bang!” a single gun sounded.

‘The V Corps and a division of Hancock will support you.’

His last sentence was caught with difficulty. It was interrupted. It came out in jerks, in sections; between the acts, to speak literally. The conference was not concluded. No more at the moment was possible to be heard. The conversation could not be continued. Neither the noise nor any destruction had arrested it. Attracted by the group, it was a shot at them from a battery…The great ball went high and harmlessly struck the ground beyond. But the whizzing missile had frightened the charger of General Meade into an uncontrollable frenzy. He reared, he plunged. He could not be quieted. Nothing was possible to be done with such a beast except to let him run; and run he would, and run he did. The staff straggled after him; and so General Meade, against his own will, as I then believed and afterwards ascertained to be the fact, was apparently ingloriously and involuntarily carried from the front at the formal opening of the furious engagement of July 2, 1863.

In relating this incident to General Pleasonton, the cavalry corps commander then tarrying at Head-quarters, he told me that there was a simple explanation of the horse feature of this affair. General Meade has sent for his own horse and was impatient at the delay in bringing it to him. He had ordered it instantly. Pleasonton, who was standing near, said: ‘Take my horse, General. He is right here.’ With minds preoccupied in battle neither general stopped to “talk horse”. General Pleasonton never thought to caution General Meade not to use his curb rein. The men of the old regular army habitually used the curb. This was General Meade’s habit. This animal was bridled with a peculiar curb, which, as Pleasonton narrates, he seldom, if ever, used on this horse, reining him only by the snaffle. So it was probable that at his initial fright from the passing missile this horse suddenly felt an involuntary twitch of the curb (he was not accustomed to feel a curb bit) as the rider (Meade) may have carelessly seized his rein, and so the spirited animal made off with him.

There was no particular harm done by or to anybody in the whole affair, as far as I ever learned. But, it has always remained with me as a regretful thought that fifteen minutes longer of the presence that afternoon of the army commander near the lines, and upon the topography, which concerned the operations of the III Corps, might have made a great difference in the performances that day.”

“Two Days of War: A Gettysburg Narrative” by Henry E. Tremain. 1905 (pgs. 63-67)

Bibliography of works cited:

- The History of the Meade Post #1, G.A.R. Philadelphia. by Oliver Bosbyshell. 1889

- Life & Letters of Gen. Meade by Col. George G. Meade, Jr.; 1913

- Meade letter to Capt. Ringwalt, Sept. 24, 1864

- Philadelphia Daily Evening Telegraph, Feb. 27, 1883

- Public Spirit, Jenkintown, PA December 23, 1882 Number 485. Pg 2

- Brief Account of Old Baldy by George G. Meade (son of the General) to Meade Post #1, G.A.R. Philadelphia, March 12, 1883

- Two Days of War: A Gettysburg Narrative by Henry E. Tremain

- Equine Relics of the Civil War, Southern Cultures: Spring 2000 : Drew Gilpin Faust

- W. B. Hervey and A. C. Johnston, manuscript, 1883, Old Baldy Papers, Civil War & Underground RR Museum of Philadelphia

- ‘Old Baldy’: General George Gordon Meade’s Veteran War Horse, Michael Cavanaugh, North-South Trader (March-April 1982): 12–34

- Historic Views of Gettysburg – Illustrations in Half-Tone of all the Monuments, Important Views and Historical Places on the Gettysburg Battlefield

- Text by Robert C. [Clinton] Miller; Published by J. I. Mumper and R. C. Miller, Custodian of the Jennie Wade House, Gettysburg, Pa. Copyright, 1912, By J. K. Mumper and R. C. Miller

The histories, photos, reports and descriptions are held in the collection of the G.A.R. Civil War Museum & Library in Philadelphia, legal owners of the head of ‘Old Baldy’ now housed with the collections of the Civil War Museum of Philadelphia at the Union League Archives.